Page History

Problems can arise when the multiple parties involved in CVD function at different operational tempos. In both the vertical and horizontal supply chain cases discussed above, synchronized timing of disclosure to the public can be difficult to coordinate. The originating vendor(s) will usually want to release a patch announcement to the public as soon as it is ready. This can, however, put users of downstream products at increased risk. As a result, coordinators sometimes find it necessary to make the difficult choice to withhold notification from a vendor in a complicated multiparty disclosure case if that vendor cannot be trusted to cooperate with the coordination effort.

When One Party Wants to Release Early

In a multiparty coordination scenario, some vendors may want to release early to protect their customers. They have a good point: should Vendor A's customers be kept vulnerable just because Vendor B is taking longer to prepare its response? Yet an equally strong counterargument can be made: should customers of Vendor B be exposed to additional risk because Vendor A was faster at its vulnerability response process? There is no single right answer to this dilemma. The best you can do is keep the communication channels open and try to reduce the amount of surprise among participants. Planning for contingencies can be a useful exercise too—the focus of such a contingency should be how to respond if information about the vulnerability got out before you were ready for it.

Communication Topology

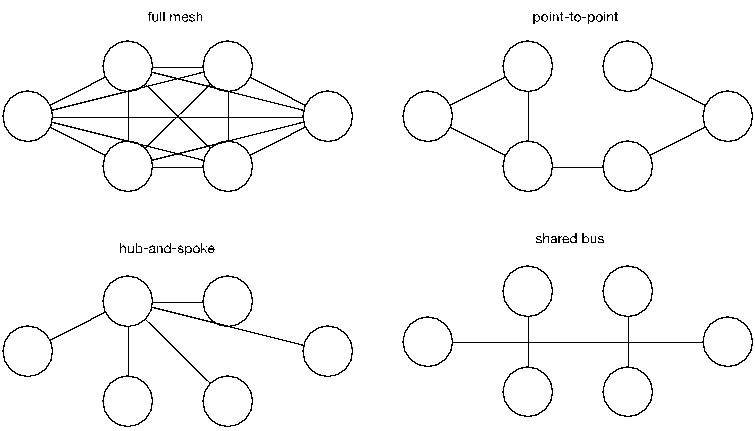

The complexity of coordination problems increases rapidly as more parties are involved in the coordination effort. Graph theory tells us the number of participant pairs increases as N(N-1)/2 for N participants. As a result, multiparty coordination using point-to-point communications do not scale well. Borrowing from communication network concepts, multiparty coordination involving more than a few participants can be improved with a shift to either a hub-and-spoke or shared-bus topology in lieu of a full mesh or collection of point-to-point communications (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Coordination Communication Topologies

The CERT/CC has historically applied a hub-and-spoke approach to coordination for cases where it was feasible to maintain separate conversations with the affected parties. Maintaining a hub-and-spoke coordination topology for each distinct case requires some forethought into tools and practices, though—you can't just carbon-copy everybody, and without good tracking tools, keeping tabs on who knows what can be difficult. A hub-and-spoke topology allows a coordinator to maintain operational security since each conversation has only two participants: the coordinator and the other party. The tradeoff is that the coordinator (hub) can easily become a bottleneck during especially active coordination situations.

Some of the larger coordination efforts we have encountered have required more of a shared-bus approach through the use of conference calls, group meetings, and private mailing lists. This approach puts the CVD participants in direct contact with each other rather than having a coordinator acting as a proxy for all communications while minimizing the communication overhead. A shared-bus approach can increase the efficiency of communications, but can on occasion make it harder to reach agreement on what is to be done.

Motivating Synchronized Release

CVD process discussions tend to focus on the handling of individual vulnerability cases rather than the social fabric surrounding vulnerability coordination we construct over time. Shifting away from the individual units of work to the social structure can suggest a way out of some of the more contentious points in any given case.

We previously described the multiparty delay problem. Game theory provides us with the prisoners' dilemma as model for thinking about this concern. The main takeaway from research into the prisoners' dilemma is that by shifting one's perspective to considering a repeated game, it's possible to find better solutions than would be possible in a one-shot game with no history. The recognition that it's a repeated game leads to improved cooperation among players who would otherwise be motivated to act solely in their own self-interest in each round [1].

One approach we've found to work is to remind the parties involved that this will likely not be the last multiparty vulnerability coordination effort in which they find themselves. A vendor that repeatedly releases early will likely get left out of future coordination efforts. Because of this, the quicker vendors might be motivated to delay so they get the vulnerability information the next time. Perhaps most important for those wanting to release early is to remember that this is a repeated game; you might be first one ready to publish this time but that may not always be the case. Consideration for the other parties involved in any given case can yield better outcomes in the long run.

In the end, everyone benefits from vendors improving their vulnerability response processes, so helping the laggards become more efficient can sometimes become a secondary goal of the coordination process.

References

- R. M. Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation, Revised ed., Basic books, 2006.